Why meme thinking within business is underused and underrated, by Amy Kean.

Allow me to use the word meme so much it loses all meaning.

And intentionally so! Because memes aren’t just a complex series of strange jokes that Generation X don’t understand.

Meme thinking is a kaleidoscopic lens through which great change can be understood in business and culture. Meme thinking, I’m certain, is also the key to successful corporate innovation.

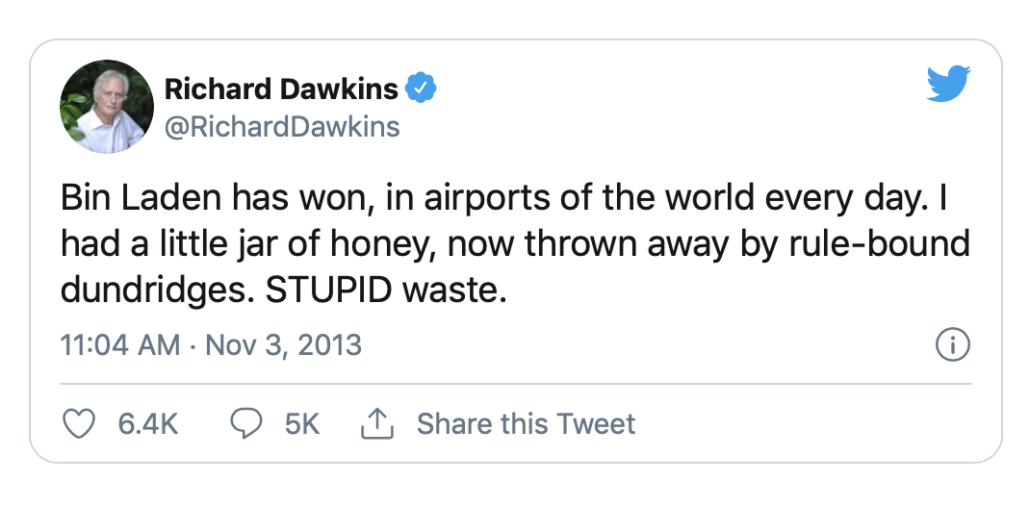

But first, so we’re all on the same page: the clever yet unpleasant atheist Richard Dawkins introduced us to the concept of memetics in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene. (Ironically, Dawkins himself became a meme thirty-seven years later when a jar of honey was confiscated from his hand luggage at JFK airport, and he blamed Osama Bin Laden.)

Memetics, as defined by Dawkins, is the study of the transference and evolution of ideas within culture. The intricacies of the concept are important: like a gene, a meme is a unit of culture (could be language, visual, entertainment, a behaviour) that is ‘hosted’ in the minds of numerous individuals. In this way it is reproduced, mutating over time, which is how we witness cultural change. It’s a fascinating space that when succinctly described, helps us understand so much about how individuals creatively interact.

Memes can be a startling and surreal mirror image of society. In a brilliant 2016 article called ‘How Harambe Became the Perfect Meme’, writer Venkatesh Rao reflected on the cultural relevance of this iconic gorilla, who was shot by rangers as they tried to save a child who’d climbed into an enclosure at Cincinnati Zoo.

But instead of just being a sad event, Harambe as an idea grew wings, and flew. He was everywhere: photoshopped and wrapped in odd and sometimes profound statements. People missed him. They cried for him. They worshipped him as a religious entity. It was weird. Says Rao:

“Harambe memes have spanned the gamut from darkly humorous to poignant, from logical to surreal. There is, it appears, no limit to range of non-sequiturs that can ride the Harambe meme. During its summer peak, merely dropping the word “Harambe” into an online conversation was sufficient to manufacture a surreal moment.”

Harambe the meme could only have happened in 2016. 2016 was a weird year. Not least because Muhammad Ali, Prince and David Bowie — unarguably three near-perfect innovators, creative geniuses (and potentially angels sent to earth to make us all up our game) died.

And then the US election happened, and the world got weirder.

By naming that period ‘the Great Weirding’, Rao in his article planted a seed that would flourish worldwide; that we are living in increasingly weird times, which call for increasingly weird measures, which result in increasingly weird behaviours.

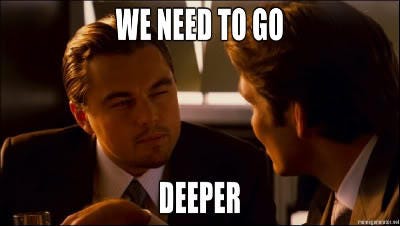

Interestingly, Rao never elaborated on what he meant by ‘the great weirding’, which allowed people to interpret and repurpose the phrase as they wished, thus creating a meme whilst talking about a meme, which is as close to Inception as you can get within meme culture… even more so than the Inception meme, below.

Rao in a Twitter thread last year referred to his intentional ambiguity, and his vision of the meme as one that “moves faster than the speed of thought”. Almost instinctive in its development.

And so, the world gets faster. And weirder.

We continue to live in The Great Weirding, yet we still don’t really know what that means. In 2020, we are no longer surprised. By anything. Since Covid-19, the use of the phrase ‘the new normal’ has been widespread and excessive, yet once again, no one can land on a universal definition. Is New Normal a meme, too?

What we do know is that ‘normal’ for businesses has shifted. We’ve seen the pivots and transformations and innovations that occurred during these last few weird months. Of course, most have been borne of necessity: the e-commerce and delivery products that emerged in record-time because they had to.

But as life starts to become more regular, how can innovators persuade scared, tired and stressed workers in any organisation to continue to embrace change, when already in 2020 they’ve seen so… much… weird?

The answer, I believe, lies in meme thinking. In a year like 2020, organisations must begin to spark memetic, contagious change, they need to encourage weird, otherwise employees will be too exhausted to implement it.

1. Innovation needs ‘hosts’

Innovation cannot be isolated to the most senior rungs of a business. When it is, this is a great way for an initiative to die on its ass. For ideas to thrive, you need a number of internal hosts with influence throughout the organisation who can guarantee both distribution and longevity. This is so, so so important.

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos expressed this very sentiment in his 2013 shareholder letter, saying:

“Decentralized distribution of innovation throughout the company — not limited to the company’s senior leaders — is the only way to get robust, high throughput innovation.”

(If only global wealth was distributed just as fairly, eh?)

2. Play and creativity makes it better

Memes trigger our natural creative urges. A meme is a result of play. It is a result of collaboration. And the more people who touch it over time, the more likely it is to see enhancement.

In these crazy days, weird innovation is all the rage. Heinz and Cadbury’s spearheaded playful innovation last year with Creme Egg Mayonnaise. And hats off to McVitie’s, whose Cherry Bakewell, Marmalade on Toast, and Strawberries and Cream Digestives were the talk of our bored lockdown lives. And I can’t have been the only one blown away by Walkers plus Nando’s, Pizza Express, Yo!, Las Iguanas and Gourmet Burger Kitchen. In fact, when I saw the multi-collab on a TV ad the other day I said “wow” out loud. That’s how cool I am.

3. It needs to be tested, always

The test and learn of memetics mimics evolution. The strong (funny, hard-hitting, memorable) survive and the weak (forgettable, heavy-handed, desperate) do not. The same applies to innovation; whether it’s a digital product or an entirely new brand, the audience must be consulted. Don’t ask people if they like it, test it on them. And experiment, and test, and test again.

Yes, frameworks are nice. Powerpoint decks are nice. McKinsey models have value. But this approach is so mad and simple, it might just work: be a meme, host the meme, live the meme, test the meme. Taste the rainbow! Or something. Just… meme.

Don’t over-protect your ideas, share them. And use ways that already work with the human brain, rather than trying to change behaviour that’s been developing since Dawkins and day one.

**Thank you to Brett Thornton for first showing me the Harambe article!